If you have ever interacted with a customer service chatbot for more than a few minutes, you have likely encountered a frustrating and familiar failure. Somewhere into the conversation, often after you have carefully explained context, preferences, or constraints, the system behaves as if none of it ever happened. You repeat yourself. The system apologizes. The cycle continues.

This behavior is usually attributed to poor prompt design or inadequate training data. In reality, it reflects a deeper architectural constraint that affects every modern large language model.

Large language models operate using an attention mechanism that processes the entire input sequence simultaneously. The computational cost of attention grows quadratically with the number of tokens, O(n²). Each token must attend to every other token. As conversations grow longer, this becomes not just slower but economically unsustainable.

A twenty-minute customer support interaction can easily exceed fifty thousand tokens. At that scale, inference latency spikes, GPU memory pressure increases, and costs compound rapidly. In production systems, this forces aggressive truncation, summarization, or outright discarding of history.

The consequences are not theoretical. In banking, a customer mentions a medical condition relevant to insurance eligibility during an early interaction, only for it to be forgotten days later. In retail, a returning customer’s preferences around price sensitivity or brand loyalty disappear between sessions. In enterprise settings, AI assistants lose track of project context across multi-day collaboration.

The paradox is striking. These systems are extraordinarily capable at understanding context in the moment, yet structurally incapable of maintaining context across time.

This is not a failure of intelligence. It is a failure of memory architecture.

Why Existing Memory Techniques Fail at Scale

Most production systems attempt to work around this limitation rather than confront it directly.

The simplest approach is summarization. Older parts of the conversation are compressed into a shorter textual summary that can be reintroduced into the model’s context window. This reduces token count, but at a cost that is often invisible. Summaries discard fine-grained detail in favor of narrative coherence. A summary stating that a customer “discussed mortgage options” collapses distinctions between fixed and floating rates, regulatory constraints, and sensitivity to interest rate changes. For downstream decision-making, these distinctions are precisely what matter.

Retrieval-augmented generation appears more principled. Past conversations are stored externally, embedded into vectors, and retrieved when new queries arrive. In practice, this introduces latency from search, ranking errors from imperfect similarity metrics, and a more subtle issue: conversational relevance is rarely lexical. A savings-rate question today may be deeply connected to a mortgage discussion weeks earlier, yet share little surface similarity. Retrieval systems retrieve documents; conversations are behavioral processes unfolding over time.

More structured approaches such as MemGPT attempt to formalize memory through explicit read and write operations. The model is instructed to decide what to store and what to retrieve. While appealing in theory, this approach embeds memory management into the model’s reasoning loop. The agent must reason not only about the task, but about how to manage its own memory. This increases cognitive load, introduces brittleness, and ties system stability to prompt discipline.

Across all these approaches, memory is treated as an auxiliary feature layered on top of language modeling. None treat memory as a first-class system with its own constraints, policies, and lifecycle.

A Different Framing: Memory as an Operating System Problem

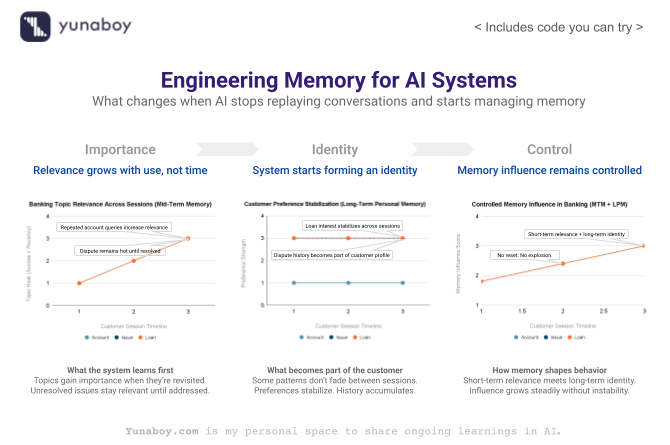

The key insight behind the paper “Memory OS: A Memory Operating System for Large Language Models”, authored by Yuhui Kang, Zhiwei Liu, Xiaojie Wang, Zhenzhong Lan, and Yang Liu, is not a novel retrieval algorithm or embedding trick. It is a reframing.

Operating systems solved an analogous problem decades ago.

Every modern computer has limited physical memory. Yet applications behave as if they have access to vast, continuous address spaces. This illusion is sustained through hierarchical memory management. Data flows between registers, CPU cache, RAM, and disk based on observable access patterns. Frequently accessed data stays close. Rarely used data is evicted. The system does not ask whether a page “should” be remembered. It measures usage and responds.

Paging algorithms such as Least Recently Used approximate optimal behavior using measurable signals like recency and frequency. The result is a system that scales automatically as workloads change, without manual intervention.

The central claim of Memory OS is that long-horizon conversational memory should be managed in the same way. The challenge is not fitting more tokens into a context window. It is maintaining the illusion of continuity under finite resources.

Memory OS as a Unified Memory Architecture

Memory OS proposes a hierarchical memory architecture that integrates storage, updating, retrieval, and response generation into a single system. Rather than treating memory as an external database queried on demand, it treats memory as a managed resource with explicit tiers and promotion policies.

At the top of the hierarchy sits short-term memory, which stores the active conversation as discrete dialogue pages. Each page contains a user query, the system response, and associated metadata such as timestamps and topic indicators. These pages are linked into dialogue chains that preserve local topical coherence. The capacity of this tier is deliberately limited. Scarcity forces structure.

When short-term memory fills, older pages are promoted into mid-term memory. This tier introduces semantic organization. Dialogue pages are grouped into topic segments using a scoring function that combines semantic similarity, typically computed via embeddings, with keyword overlap. This hybrid approach prevents semantically related conversations from being fragmented while avoiding the collapse of unrelated content into generic summaries.

Mathematically, the assignment of pages to segments is governed by an F-score that balances semantic and lexical similarity. Thresholding ensures that only sufficiently related content is grouped, preserving topical integrity.

Mid-term memory is managed using a heat-based eviction policy. Each segment accumulates heat as a function of access frequency, segment size, and temporal decay. A simplified representation of this can be written as:

Heat = α · access_count + β · segment_size + γ · exp(−Δt / τ)Here, access_count captures how often the segment has been retrieved, segment_size reflects informational richness, and the exponential decay term penalizes staleness. The constants α, β, and γ weight these contributions. Importantly, eviction is not based solely on recency. A large, frequently accessed topic can remain hot even if individual pages are old.

When mid-term memory reaches capacity, cold segments are evicted and archived.

Beneath this sits long-term personal memory. This tier does not store raw dialogue. Instead, it stores extracted, durable signals: stable user attributes, evolving preferences, and lightweight trait representations. For an agent, it stores interaction patterns specific to that user. These representations are probabilistic and inherently noisy. The paper does not claim deep psychological modeling. The objective is behavioral consistency across sessions.

From Research Results to Real Workloads

The paper evaluates Memory OS on long-context benchmarks such as LoCoMo and GVD, demonstrating significant improvements in memory accuracy, temporal reasoning, and response quality compared to prior systems. Equally important is efficiency. Memory OS achieves these gains while consuming far fewer tokens per response, reducing inference cost and latency.

From an industry perspective, these results matter not because of benchmark scores, but because they alter feasibility boundaries.

In banking, customer relationships unfold over weeks or months. Preferences, risk tolerance, and life events evolve gradually. A system that can maintain continuity without replaying entire histories enables assistants that behave consistently without incurring runaway costs.

In retail, personalization depends on remembering patterns rather than transactions. Price sensitivity, brand affinity, and return behavior emerge over time. Memory OS allows these signals to persist without bloating prompts or relying on brittle retrieval heuristics.

In both domains, the distinction between remembering everything and remembering what matters is critical. Memory OS formalizes that distinction.

Why This Is Not Just Better Retrieval

It is tempting to view Memory OS as a sophisticated retrieval layer. This misses the point.

Retrieval systems answer the question: “What past information is similar to this query?”

Memory systems answer a different question: “What information should remain accessible over time?”

The former is reactive. The latter is systemic.

By structuring memory as a hierarchy governed by observable usage patterns, Memory OS replaces ad-hoc heuristics with emergent behavior. The system adapts because access patterns change, not because rules are rewritten.

Implications for Regulated Domains (Extrapolation)

The paper itself does not evaluate regulatory compliance. However, the architecture has clear implications for domains such as banking and healthcare, where deletion, retention, and auditability are mandatory.

Tiered memory aligns naturally with regulatory requirements. Active conversational memory can be cleared quickly. Long-term personas provide explicit deletion points. Archived segments can be timestamped and governed by retention policies. This stands in contrast to vector-based retrieval systems, where deletion is probabilistic and difficult to audit.

Memory OS does not guarantee compliance. What it offers is architectural clarity. Compliance becomes expressible in system design rather than enforced through operational patches.

The Deeper Shift

The significance of Memory OS lies not in any single algorithm or benchmark improvement. It lies in reframing long-term AI memory as a systems problem.

Prompt engineering cannot solve memory continuity. Larger context windows cannot scale indefinitely. Retrieval alone cannot capture behavioral evolution. What is required is the same principle that made modern computing possible: hierarchy, scarcity, and eviction.

Operating systems do not remember everything. They remember just enough, systematically.

Memory OS applies this philosophy to language models. In doing so, it moves AI systems closer to sustained interaction over time — not by making models smarter, but by making memory boring, predictable, and governed by structure.

That is the quiet, consequential contribution of the paper.

Code Walkthrough: Demonstrating Memory as Infrastructure in Banking

This section translates the ideas discussed in the blog into an executable banking walkthrough.

The goal is not to build a chatbot, but to demonstrate how memory architecture changes system behavior in a regulated, longitudinal domain like banking.

Section 1 — A Banking Relationship Is Not a Session

Banking interactions unfold across days and weeks. Risk, disputes, and preferences are not resolved in a single conversation and cannot be treated as short-lived context.

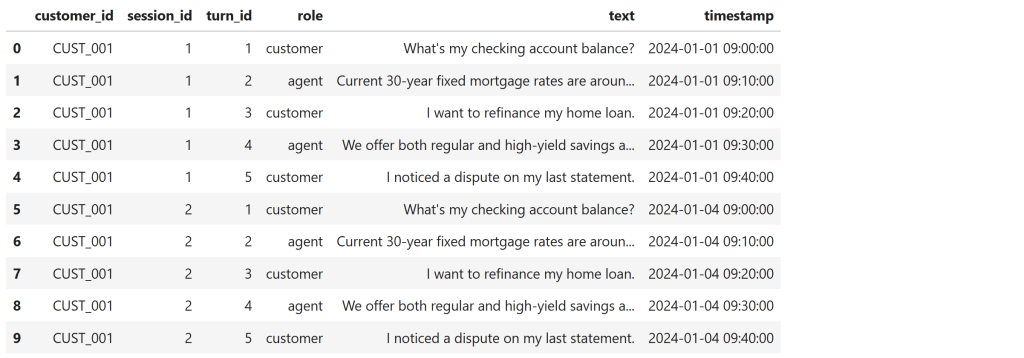

Step 1 — Create a multi-session banking interaction timeline

import pandas as pd

from datetime import datetime, timedelta

CUSTOMER_ID = "CUST_001"

START_DATE = datetime(2024, 1, 1, 9, 0, 0)

SESSIONS = 3

TURNS_PER_SESSION = 5

customer_queries = [

"What's my checking account balance?",

"Tell me about current mortgage rates.",

"I want to refinance my home loan.",

"What savings account options do I have?",

"I noticed a dispute on my last statement."

]

agent_responses = [

"Your checking account balance is $3,245.",

"Current 30-year fixed mortgage rates are around 6.5%.",

"Refinancing options depend on credit score and loan tenure.",

"We offer both regular and high-yield savings accounts.",

"Your dispute has been logged and is under review."

]

records = []

for session_id in range(1, SESSIONS + 1):

session_start = START_DATE + timedelta(days=(session_id - 1) * 3)

for turn in range(TURNS_PER_SESSION):

timestamp = session_start + timedelta(minutes=turn * 10)

role = "customer" if turn % 2 == 0 else "agent"

text = customer_queries[turn] if role == "customer" else agent_responses[turn]

records.append({

"customer_id": CUSTOMER_ID,

"session_id": session_id,

"turn_id": turn + 1,

"role": role,

"text": text,

"timestamp": timestamp

})

bank_df = pd.DataFrame(records)

bank_df.head(10)

What the output shows

- The same customer interacting across multiple sessions

- Sessions separated by realistic time gaps

- Repeated banking intents (account, loan, dispute)

This timeline is the ground truth that any memory system must respect.

Section 2 — Stateless Banking Assistant (Baseline Failure)

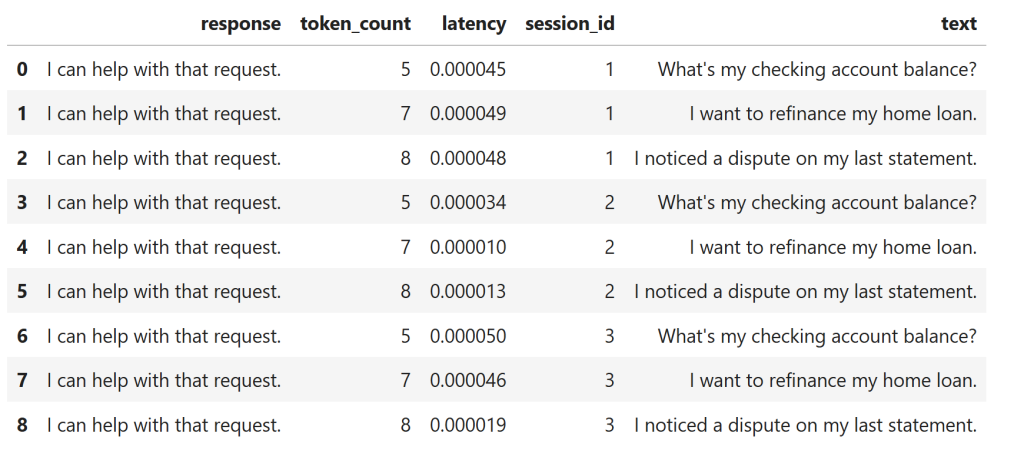

We begin with the most common architecture: every request is processed independently.

Step 2 — Simulate a stateless banking assistant

import random

import time

def stateless_banking_agent(query):

response = "I can help with that request."

token_count = len(query.split())

latency = random.uniform(0.00001, 0.00005)

time.sleep(latency)

return {

"response": response,

"token_count": token_count,

"latency": latency

}

stateless_results = []

for _, row in bank_df.iterrows():

if row["role"] == "customer":

out = stateless_banking_agent(row["text"])

out["session_id"] = row["session_id"]

out["text"] = row["text"]

stateless_results.append(out)

stateless_df = pd.DataFrame(stateless_results)

stateless_df

What the output shows

- Identical responses regardless of session

- No awareness of prior interactions

- Token usage stays small, but context is completely lost

This is the forgotten customer problem in its purest form.

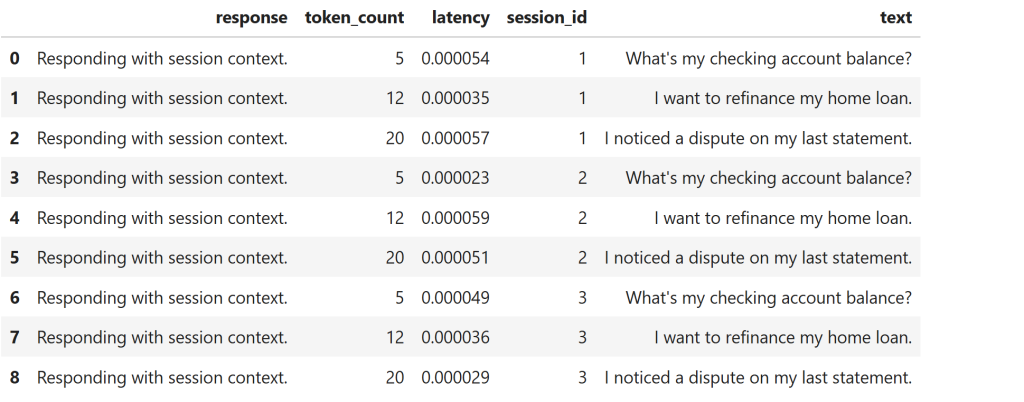

Section 3 — Session-Bound Memory (Call-Center Style STM)

Many banking systems improve on this by remembering context within a single call.

Step 3 — Add short-term, session-bound memory

STM = {}

def stm_banking_agent(customer_id, session_id, query):

if (customer_id, session_id) not in STM:

STM[(customer_id, session_id)] = []

session_memory = STM[(customer_id, session_id)]

context = " ".join(session_memory + [query])

response = "Responding with session context."

token_count = len(context.split())

latency = random.uniform(0.00002, 0.00006)

time.sleep(latency)

session_memory.append(query)

return {

"response": response,

"token_count": token_count,

"latency": latency

}

stm_results = []

for _, row in bank_df.iterrows():

if row["role"] == "customer":

out = stm_banking_agent(

row["customer_id"],

row["session_id"],

row["text"]

)

out["session_id"] = row["session_id"]

out["text"] = row["text"]

stm_results.append(out)

stm_df = pd.DataFrame(stm_results)

stm_df

What the output shows

- Token count grows within a session

- Memory resets across sessions

- Context improves locally but disappears after the call ends

This mirrors traditional IVR and contact-center architectures.

Section 4 — Topic-Aware Banking Memory (Mid-Term Memory)

Memory OS introduces the idea that related interactions should stay together, regardless of time.

Step 4 — Organize banking interactions by topic

MTM = {}

TOPIC_KEYWORDS = {

"balance": "Account",

"checking": "Account",

"mortgage": "Loan",

"refinance": "Loan",

"savings": "Savings",

"dispute": "Issue"

}

def infer_topic(text):

for keyword, topic in TOPIC_KEYWORDS.items():

if keyword in text.lower():

return topic

return "General"

def mtm_banking_agent(customer_id, session_id, query):

topic = infer_topic(query)

if customer_id not in MTM:

MTM[customer_id] = {}

if topic not in MTM[customer_id]:

MTM[customer_id][topic] = {

"turns": [],

"heat": 0

}

topic_memory = MTM[customer_id][topic]

context = " ".join(topic_memory["turns"] + [query])

response = f"Responding using topic memory: {topic}"

token_count = len(context.split())

latency = random.uniform(0.00003, 0.00007)

time.sleep(latency)

topic_memory["turns"].append(query)

topic_memory["heat"] += 1

return {

"response": response,

"token_count": token_count,

"latency": latency,

"topic": topic,

"heat": topic_memory["heat"],

"session_id": session_id,

"text": query

}

mtm_results = []

for _, row in bank_df.iterrows():

if row["role"] == "customer":

out = mtm_banking_agent(

row["customer_id"],

row["session_id"],

row["text"]

)

mtm_results.append(out)

mtm_df = pd.DataFrame(mtm_results)

mtm_df

What the output shows (Memory OS behavior)

- Topics like Account, Loan, Issue persist across sessions

- Heat increases with repeated access

- Context grows by relevance, not chronology

👉 This directly maps to the Mid-Term Memory (MTM) tier in the paper.

Section 5 — Persistent Customer Profile (Long-Term Personal Memory)

At this stage, the system remembers topics — not the customer.

Step 5 — Extract durable banking signals

import re

LPM = {}

def extract_banking_facts(text):

facts = {}

if "dispute" in text.lower():

facts["has_dispute_history"] = True

if "refinance" in text.lower():

facts["loan_refinance_interest"] = True

if "savings" in text.lower():

facts["savings_interest"] = True

return facts

def lpm_banking_agent(customer_id, topic, query):

if customer_id not in LPM:

LPM[customer_id] = {

"preferences": {},

"persona": {}

}

prefs = LPM[customer_id]["preferences"]

prefs[topic] = prefs.get(topic, 0) + 1

facts = extract_banking_facts(query)

LPM[customer_id]["persona"].update(facts)

response = "Responding with long-term customer memory."

return {

"response": response,

"topic": topic,

"preferences": prefs,

"persona": LPM[customer_id]["persona"]

}

lpm_results = []

for _, row in mtm_df.iterrows():

out = lpm_banking_agent(

CUSTOMER_ID,

row["topic"],

row["text"]

)

lpm_results.append(out)

lpm_df = pd.DataFrame(lpm_results)

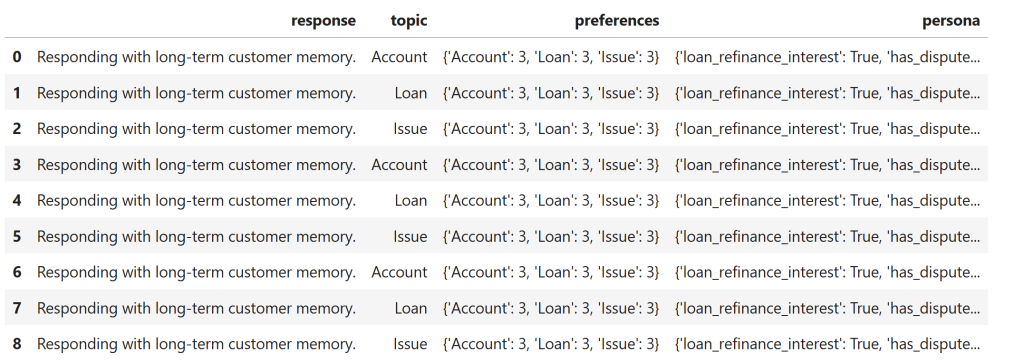

lpm_df

What the output shows (Memory OS behavior)

- Preferences stabilize across sessions

- Persona facts persist even when topics change

- Memory becomes compact and durable

👉 This corresponds to Long-Term Personal Memory (LPM) in the paper.

Section 6 — Combining MTM and LPM (Memory OS in Action)

Memory OS does not replace one memory with another. It combines tiers.

Step 6 — Compute combined memory influence

combined_records = []

for _, row in mtm_df.iterrows():

topic = row["topic"]

mtm_heat = row["heat"]

lpm_pref = LPM[CUSTOMER_ID]["preferences"].get(topic, 0)

combined_score = 0.6 * mtm_heat + 0.4 * lpm_pref

combined_records.append({

"session_id": row["session_id"],

"topic": topic,

"mtm_heat": mtm_heat,

"lpm_pref": lpm_pref,

"combined_score": combined_score

})

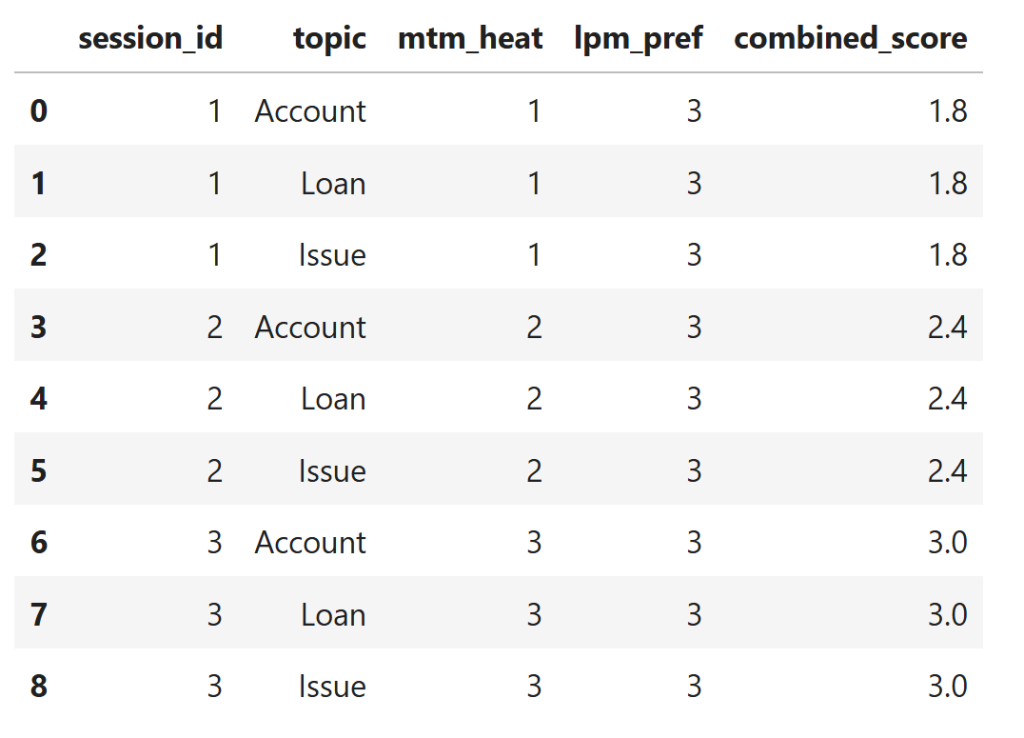

combined_df = pd.DataFrame(combined_records)

combined_df

What the output shows (key insight)

- No reset across sessions

- No unbounded growth

- Stable, interpretable memory influence

👉 This is the OS-style “heat-based” memory control described in the paper.

This Walkthrough Demonstrates

- Stateless systems forget customers

- Session memory fixes only local coherence

- Topic memory introduces continuity

- Persona memory stabilizes identity

- Hierarchical memory changes system economics

This code section is not a chatbot demo. It is an executable argument that memory in banking AI systems must be treated as infrastructure, not prompt engineering.